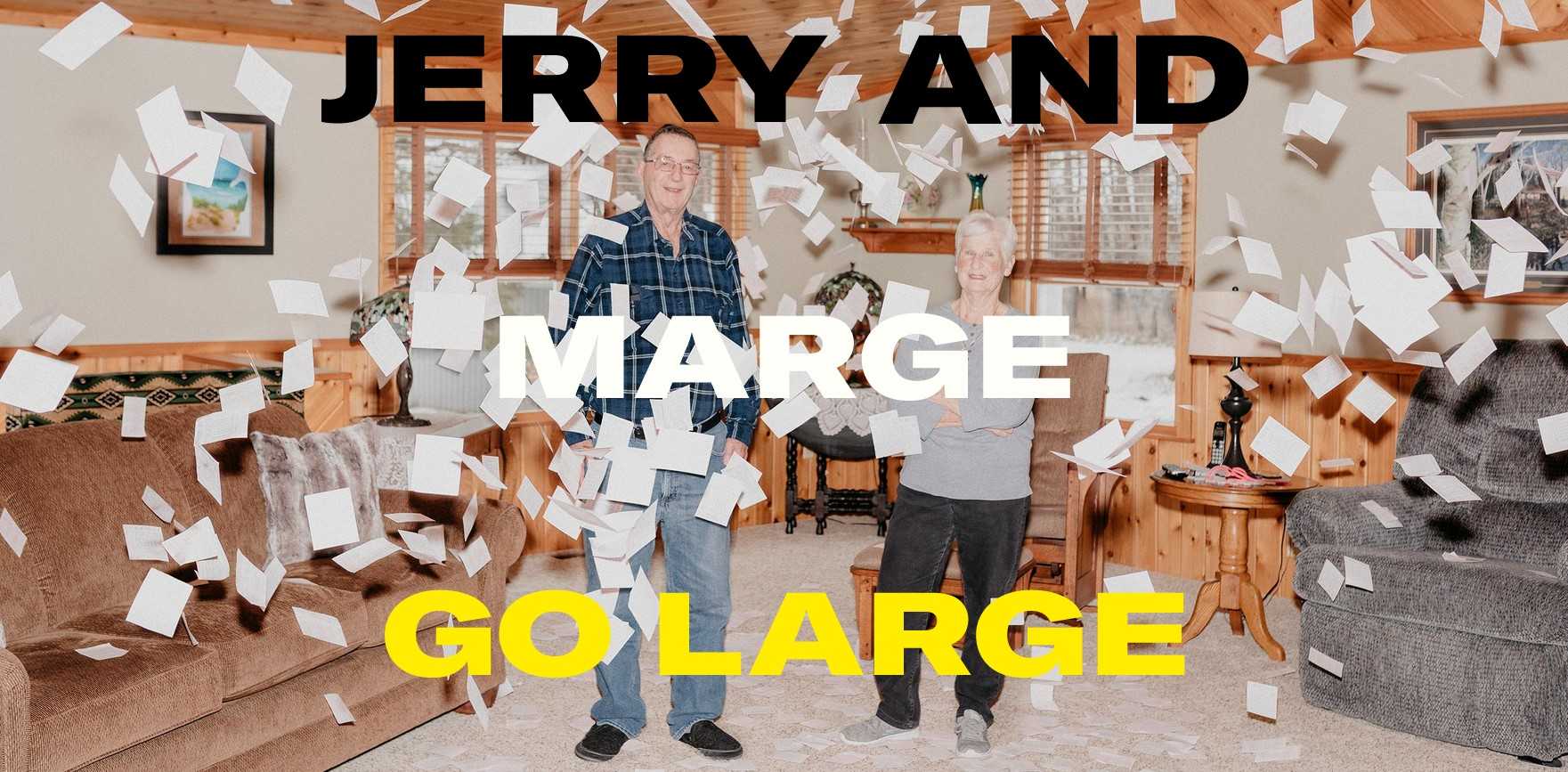

Jerry and Marge Golarge

The US citizens love to play the lottery: Americans spend $80 billion a year on tickets, compared with just $11 billion on going to the movies. Not surprisingly, there are also those who try to cheat the system.

The crunchy cipher

Gerald Selbee has always had a love of maths and riddles. At school the boy’s talents were long overlooked and he was even left behind because of dyslexia which prevented him from reading and writing properly. However, at age 14 the test showed that Jerry can solve problems at the level of a first-year maths college student. He graduated from high school without much regalia, married a beautiful classmate, Marge, and went to work as a materials scientist in a cereal factory. His main job was to extend the shelf life of his cereal and come up with packaging that would keep it dry and crispy for as long as possible.

Jerry compared his manufacturer’s cereal and their main competitor’s daily – drying and heating them and then weighing them, comparing moisture levels. The work was not too interesting, so one day out of boredom he became interested in the set of numbers that the competitors printed on the bottom of the packaging. The cipher unambiguously indicated not the time and region of manufacture, and Jerry began to look for what the numbers had in common. He spent several days in the shop comparing packages and eventually figured out how the cipher worked and was able to trace competitors’ production back almost to a particular spike. Unfortunately, managers did not appreciate the young man’s discovery: after all, he worked in cereal production, not cars or aeroplanes. But he was proud to have discovered this little secret.

Jerry then moved through a number of jobs at the factory: from chemist to packaging designer, from programmer to shift manager. And all the while he was constantly learning: taking evening courses and going to the library. Each time he immersed himself in his interests and took the whole family with him. During his fascination with mycology, Gerry and his six children searched for morels in the nearby woods, and when he became obsessed with geology, the whole family went camping in search of fossils. When his eldest son Doug entered high school, his father asked for help with a crazy new idea: he would buy coins from banks by face value and check to see if any numismatic rarities were mistakenly included. They spent hours poring over five-cent coins in front of the TV and ended up making about six thousand dollars on it. “If he was into something, he threw himself headlong into it. If he was suddenly interested in string theory and black holes, before you knew it you had all these Stephen Hawking books lying around,” my son said.

Money out of thin air

Jerry and his wife Marge eventually moved to the small Michigan town of Evart, which was home to about two thousand Americans. He had long considered buying a small shop, studied all the offers carefully, and concluded that Evart was the perfect place. Their shop on the main street was soon frequented by everyone in town: the husband bought cigarettes and alcohol, while his wife arranged the goods on the shelves, kept the books and placed small impulse purchases like sweets on the till. They worked from seven in the morning until midnight even at Christmas.

At one point he installed a lottery machine in the shop, the only one in town and one of the few in the county. Everyone played: one of the regular customers, whom he and his wife called ‘six packets of cigarettes’, had to be renamed ‘six packets of cigarettes and five tickets’. Soon the Selbees were selling tickets for about $300 000 a year and were getting $20,000 of that.

The Selbees did not drink, did not smoke and hardly ever played the lottery: Jerry only occasionally allowed himself to buy a couple of tickets. The lottery machine drew customers to them, and they used it to earn money to build an extension to the shop and hire another employee. “It was easy money,” Jerry admitted, but the family spent it wisely: they were able to pay for the higher education of all six children.

First steps

In 2000, when their children were grown and separated, the Selbees decided to retire. And three years later, when Jerry was 64, he finally found a mystery to match. One day in a shop he was handed a brochure describing a lottery that asked him to guess a sequence of numbers. At that moment, as with the box of cereal, something clicked in the man’s mind. He realised how he could make millions, but had no idea what the consequences would be.

The lottery was called Winfall. A player would buy a ticket for one dollar and enter six numbers into it: from 1 to 49. Those who guessed all six were entitled to a jackpot of at least two million dollars. Smaller winnings could go to those who guessed five, four, three and two numbers. What Jerry particularly liked was the roll-down concept: if the jackpot remained unplayed, every six weeks or so all the money was distributed to other winners: a larger portion went to those who guessed five numbers, a smaller portion to those who managed to guess four numbers, and so on. As Jerry studied the terms and amounts of the winnings, he realized that one dollar spent on tickets was mathematically equivalent to more money, as the prizes increased by a factor of about ten.

Jerry got excited about the idea of making money from lotteries, but he didn’t know how his wife would react to the venture. She had always been pragmatic and had brought her husband down to earth more than once and also believed that money could only be made by hard work. He realised that he would need ironclad proof, and he himself did not yet believe that he had managed to spot a loophole that hundreds of lottery employees had overlooked in a couple of minutes. So he decided to test the hypothesis secretly from his wife: the first time he didn’t buy tickets and did the calculations, comparing his results with the real winnings.

After a month, he decided to try the method in practice. He went to a neighbouring town to avoid answering inconvenient questions from acquaintances, and spent $2 200 on tickets, each time letting the computer choose the winning numbers for him. A few days later, he counted all the matches (he was able to guess two, three and four numbers) and got a win of $2 150, leaving him with a small loss. He did not tell the authorities about the crack in the system: Jerry was sure that they were already aware of it, and were just using it to get people to buy more tickets.

Jerry was not upset and concluded that he had simply bet too little money, and thus the odds of winning did not equal the odds of losing. The next time he bought $3 400 worth of tickets. It wasn’t easy to go through them – especially since he was doing it right in the shop so Marge wouldn’t catch him playing. But the eye-rolling was worth it: he won $6 300, making a 46 percent profit. The next time, he spent eight thousand dollars on tickets and won $1 500.

The company

Jerry decided to confess to his wife during a picnic with friends after all. He said he was playing the lottery, but he knew how to win. He has a system and has won five-figure sums before. Marge was silent and then smiled, knowing her husband’s love of mathematical riddles. From then on, she printed tickets with him: they would go to the shops in the morning and spend hours printing thousands and thousands of tickets. The local shopkeepers knew the pair and did not discourage their hobby in any way, and they ignored questions from vain gawkers.

Then they sorted the tickets into stacks of five thousand dollars and took turns laying them out all over the living room in front of the television. They sorted through tens and sometimes hundreds of thousands of tickets and sorted by the number of winning numbers (from two to five). Then they repeated the procedure again to make sure they hadn’t missed anything. “It looked very tedious and boring, but they had a very different attitude. They were so trained that they spent less than a second on the ticket,” says their daughter Donna. Several times she tried to help them, but every time she gave up: While she was checking one ticket, each of the parents had time to check ten.

At first, the children thought Gerry had gone mad. “Dad kept saying it was school level maths, but I was always bad at maths, so I didn’t understand anything,” Donna admitted. But her parents genuinely enjoyed what was going on and got bored in the weeks when there was no roll down.

But soon the children joined their father’s strange hobby. He noticed that companies were often allowed to play the lottery and decided that the state was literally encouraging people to play in groups and place big bets. Six months after his first win, he encouraged all six children to play with him. The first time they bet $18 000 and lost almost all their money because someone guessed all six numbers and hit the jackpot. But Jerry managed to convince the family to do it again and a couple of times later they were all winners.

Jerry soon set up a company and chose the most boring name for it: GS Investment Strategies LLC. He sold shares at $500 each to children, friends and acquaintances: in the end there were about 25 people on the list of shareholders (and in fact players). The company existed only on paper – in reports in which Jerry indicated how much money was spent on tickets, how much was won and how much tax had to be paid on it. The sole purpose of this legal entity was to play the lottery.

Business was booming: by 2005, GS Investment Strategies LLC had experienced 12 weeks of roll-outs, and the stakes increased along with the winnings. First they won 40,000, then 80,000, then 160,000… Marge kept the savings in a savings account, Gerry bought a new car and a camping trailer. Soon he started buying gold and silver in coins to stockpile in case of inflation and financial crisis.

Competition in Massachusetts

But in May 2005, Winfall was closed without warning. The authorities attributed this to a downturn in ticket sales. Jerry, as well as the rest of his family, were very upset. But the sadness didn’t last long: one of their lottery group members discovered a similar game in Massachusetts. Some of the conditions were different, for example the ticket cost two dollars instead of one, you could choose numbers from 1 to 46, and the roll-down was announced when the jackpot reached two million.

Jerry realized that he could get back to his hobby, the only problem was that Massachusetts was 700 miles away from Ewart. He had no acquaintances there, and the salesmen were unlikely to allow him to stand for hours printing tickets. Nevertheless, he took his chances and went there not yet knowing that he would face competition.

A Massachusetts Institute of Technology student named James Harvey was about to cross the inventive old man’s path. For a study project, he studied all the lotteries in the United States, comparing which one was most likely to win. Of course, he couldn’t miss out on the Massachusetts version of Winfall, rightly concluding that two dollars a ticket turns out to be far more expensive in terms of maths during roll-your-own week. Over a few days, Harvey managed to convince about 50 students to chip in $20 each to buy 500 tickets for $1,000. They ended up winning 3,000, and each was able to win back the money and get an extra $40.

The lucrative terms attracted not only them, but also biomedical scientist Ying Zhang. He started looking into lotteries after arguing with friends that it was impossible to win in them. However, a loophole in Winfall made him rethink his views to such an extent that he soon quit his job and started his own gaming club. They bought $300-500,000 worth of tickets and he kept them in boxes in the attic until one day they broke through his ceiling.

Meanwhile, the engineering students set up a pseudo-company called Random Strategies LLC, with about 50 people as shareholders, including professors. They bought $600,000 worth of tickets each roll-over week. Unlike old man Selby, they didn’t trust the entry of numbers to a computer, but did this manually to avoid repetition. This increased the probability of winning, but the students sat for weeks and manually filled in the lottery tickets.

But the Selbees wasted no time either, with an elderly couple coming to Massachusetts during each Roll Down drawing. The week before the roll-down, they would start printing tickets at 5:30 a.m. and finish at 6 p.m. After the winning combination was published, they would spend all day sorting out tickets at the hotel. They had to work 10 days, 10 hours each, to sort through $70 000 worth of tickets. They would only leave the room to have lunch. Then they would cash their winnings and drive home, taking all the losing tickets. They hid them in a barn in plastic containers, and there lived raccoons, which they planned to flush out to the tax auditors if necessary.

That’s how they lived for the next five years. Jerry didn’t think he was doing anything illegal. One day a police officer came by on a complaint from a neighbour, but also found no wrongdoing in their actions. Despite the fact that the Selbys were making millions, it never even occurred to them to lavish money and live life to the fullest. They lived in the same house, drove an old car, and Marge continued to wash dishes by hand and had no idea they could buy a dishwasher or hire a housekeeper. The money was being spent on her grandchildren’s education.

Beginning of the end

The shareholders idolized Jerry’s resourcefulness, but constantly asked him how much longer he was going to keep playing. The band lost money only three times in its existence: most of all in 2007, when they took a $360 000 loss because of a correctly guessed jackpot. But literally on the next rollover, Jerry’s company bounced back. Jerry claimed that he was going to “milk this cow for as long as she had milk”.

However, the competitors didn’t doze off, and one day the engineering students realised that their profits were no longer growing because the winnings were being divided among the three factions. Harvey then decided to pour so much money into the lottery to cause a rollover artificially, without giving competitors time to purchase tickets. When the jackpot was $1.6 million, his faction put $1.4 million into the lottery, which was more than enough for an unscheduled rollover. The others didn’t have time to react and he got more than $700 000 in benefits.

Of course, lottery employees couldn’t help but notice the abnormal jump in bets and guessed exactly what had happened. However, instead of imposing fines, they simply upgraded the system to report abnormally high bets so that they had the opportunity to alert other players.

When Jerry found out what had happened, he was furious. He vowed that he would not let himself be cheated next time. So on Christmas Eve he travelled alone to Massachusetts, where he managed to print $45,000 worth of tickets in one day. As he was typing the last ones, a knock sounded at the door. It was a representative of the techies. He suggested that Selby team up and take turns playing roll-ups, but the old man refused, deeming it unethical. That time, the tech students repeated the old trick again, the alert system didn’t work, and a concerned Jerry got a $200 000 profit in time.

Boston Globe journalist Andrea Estes noticed something amiss with the lottery in 2011. She scrutinized the lists of regular winners and found tech, biomed, and Selby. No one would talk to her and she had to go to the authorities. “They were well aware of what was going on but made round eyes when I informed them.” However, the journalist’s action had consequences: seven shops that were selling too many tickets were shut down.

But this was not enough for her and she released a sensational investigation in which she made all the gaming groups look like villains. She accused them of taking single players’ money and denying them a chance to win. “Lottery players have a right to expect their money to go for the good of the state and not into the pockets of rich people who have figured out how to cheat the system,” Estes wrote. Jerry was extremely upset as he did not consider himself a cheat. Besides, some of the money he paid did go to the state. Giving up the game wasn’t easy: he and Marge tried to find another shopkeeper who would agree to print unlimited tickets for them. But he called the cops. And Jerry had to explain that he was a law-abiding businessman who paid his taxes. The policemen laughed and let him go.

The company had played a total of 55 times in eight years, 12 in Michigan and 43 in Massachusetts. In total, they bought $19.1 million worth of tickets, won $26.85 million and made a net profit of $7.75 million.

As a result of the investigation, all of the gaming groups were found guilty of only minor infractions like printing tickets at prohibited times for sale. The police concluded that their activity had no effect on the chances of single players winning, but their maniacal persistence had resulted in a $120 million boost to the state’s budget over seven years.

Learn more interesting facts about lotteries and bet online on 49’s uk.

Please, leave a comment